imitation is the white$t form of flattery

November 6, 2013 § Leave a comment

with a line from my poem “Did anyone ever tell you that you look like Kreayshawn?”

[image: hand holding the earth, the word “IMITATION” is visible across the earth in a thick letters with images of different pop stars from history. on the bottom are the words “IS THE WHITEST FORM OF FLATTERY.”] (thanks fabian romero for reminding me to caption (and writing this one) for people with vision loss who use assistive technology)

Good White Person

September 13, 2011 § 8 Comments

Yes, ol’ fashioned racism can and does get to me. Those racial slurs as I ride my bicycle, being the only one followed by the security guard, or the never-really-random airport search, but most days, if I had to choose my direct racist experience, I’d rather any of the above over encounters with a Good White Person.

If you’re a POC, you probably know at least one of these Good White People! If you’re white and reading my blog, maybe you are one; a well intentioned whitey. You’re ‘on my side’, right? You figured out racism is ‘bad’ so now you’ve joined the fight against racism! Maybe you work in a social enterprise, for a charity, with refugees, or Indigenous people, or in the multi-cultural arts. You’re proud of yourself for your many years of human rights work. You’ve claimed your anti-racist identity, you have friends and maybe even lovers who are people of colour, so how could you possibly be racist?

How could you NOT be racist? We have been raised in a white supremacy and we have all internalised racism. We are all racist.

I don’t have the emotional or political energy for friends and acquaintances who express that they are hurt and offended that I’ve inferred that they are racist by critiquing their behaviour or by simply withdrawing from their company. I know that it hurts to feel admonished or abandoned, but this is not comparable or relevant to the hurt and betrayal I feel by people who have tried to contextualise the racist behaviours I experience in terms of the person who has enacted racism’s ignorance, insecurities, or good intentions (which are factors in their behaviour, but don’t alter my experience of their behaviour as racism). This justification de-validates my experience, and though I remind myself that friends are well intentioned in trying to comfort me by convincing me that I needn’t feel bad because nobody meant any harm, they are silencing me as a person of colour, re-centering the experience around whiteness, and being complicit in white supremacy. In contrast, I emphasise how empowering it has been to share experiences of racism and have my anger and sense of alienation validated by others. This has been infinitely more ‘comforting’ than the friends who have had a ‘Don’t worry about it’ attitude. That’s their privilege not to worry about something that permeates all aspects of my daily, lived experience.

I do have white friends who ‘worry about it’. And I mean, beyond white guilt. White guilt doesn’t really help me in itself, it doesn’t help me have a less racist experience of the world. Articulation of white guilt re-centers discussion of racism around white experience, and it puts pressure on POCs to reassure white people’s feelings. I have been generous enough to articulately delineate to people that I care about, how they have enacted privilege on me and had them shut down, be paralysed by guilt that I want nothing to do with. If they use their guilt to be self-aware and conscious of their privilege, if it provides some ongoing motivation for them to critically reflect on and deconstruct their place in white supremacy and to critically engage in the future, then that isn’t bad, but they shouldn’t expect congratulations for it. They should be grateful I expended energy and emotionally risked myself to critique them, because there is less risk and more empowerment in sharing experiences and having them validated, than in educating white people, especially individually.

I operate with great suspicion around white people and white dominated collectives and spaces that claim anti-racist motivations. It so often seems that embracing diversity is seen as a magical recipe for equality when it’s no guarantee that everyone’s experience in the ‘diverse group’ will be an equal experience. It means there’s a complicated mix of power dynamics to do with race, class, gender, able-bodiedness, etc that need be acknowledged and constantly addressed. I’m not going to applaud them for their embracement of diversity, I’m going to wonder about how those dynamics play out and doubt that those from ‘marginalised groups’ feel empowered in the situation. Just because the doormat, the signage, the mission statement or they personally say ‘You’re welcome here’, does not mean that I have automatically been made to feel welcome, and when the racisms I critique are condoned or denied, that welcome means nothing.

Don’t assume because I’m in your establishment, party, group, band, bed, or friendship, that our experience of that situation is equal, when we didn’t even come to the situation from equal grounds. You asserting to me, especially in the face of me critiquing your privilege and your racisms, that you consider ‘all people equal’ and that you ‘treat all people the same’, denies my experience within, and affirms to me your complicity in, white supremacy. We do not have an equal experience of the world and so your supposed equal treatment can never be experienced equally. For example, a person (such as one of colour) who has had their body devalued, made both invisible and hyper-visible, who has been constantly other-ed, is not going to experience non-consensual touch in the same way as those subject to less consistent other-ing.

I’m speaking from my lived experience as a marginalized person who has been in situations that I was not forced into, putting in energy that was not asked of me, and consistently adapting though it was rarely literally demanded of me to do so. I realise, mostly in retrospect, how privilege has played into my relationships, collaborations and other experiences. And I try to understand why those who have enacted privilege on me do not understand my anger and sense of betrayal that is often catalysed when adaptation is consistently not reciprocated even in crucial times. Perhaps neither of us acknowledged the ongoing implicit power dynamics; my adaptation nor how that adaptation is part of a lifetime of my being conditioned to adapt, and their lifetime of having those without their privilege adapting to them. Of course, the dynamics are not just of race, but class, gender, sexuality and many other complexities. I know I have unwittingly enacted privilege on those I care about. I’m grateful to people who have pulled me up because it shouldn’t be up to them to challenge me, I need to be self-aware and initiate change in myself. And I’m thankful and inspired if they’re still in my life, because I know continued engagement with people who un-intentionally de-validate your experience is a generosity I haven’t lately been feeling capable of myself.

I would prefer not to operate on a high level of distrust towards most white people I encounter, but it seems a lot healthier than consistently feeling betrayed. You can’t just say ‘trust me’; you have to earn trust and keep it alive. As a person of colour, I know that first hand, as trust is not something given freely to people of colour by white supremacy. Yet I am constantly expected to offer my trust, without critique, to white people, and if I do not, then I am pitied, feared, despised or dismissed for my distrust, including by some other people of colour. It’s as if I should know, there are ‘bad’ racist people out there but there are white people who have nobly chosen to be saviours of people of colour, when they didn’t even have to be! That I should realize I need gratefully congratulate them for deciding to be a Good White Person.

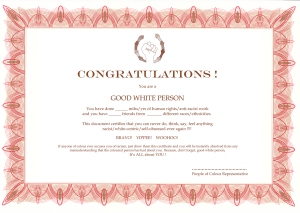

So, here’s a certificate for all the Good White People out there, born out of an email exchange with Wai Ho of Mellow Yellow blog (thanks Wai!). So, Good White People, if you really want to fight racism and help people of colour then send $10 and I’ll send you an authentic, signed certificate in the post. All proceeds to People of Colour.

[photo description: certificate with fancy border. at top centre is a drawn logo of a white fist surrounded by a wreath of smaller various coloured hands. underneath reads “CONGRATULATIONS! You are a GOOD WHITE PERSON. You have done ___ months / years of human rights / anti-racist work and you have ___ friends from ___ different races / ethnicities. This document certifies that you can never do, think, say, feel anything racist / white-centric / self-obsessed ever again !!!! BRAVO! YIPPEE! WOOHOO! If anyone of colour ever accuses you of racism, just show them this certificate and you will be instantly absolved from any misunderstanding the coloured person* has had about you. Because, don’t forget, good white person, It’s ALL about YOU!” Below in bottom right corner is a line for a signature, under which reads “People of Colour Representative”]

*this certificate was made in collaboration with Wai Ho, based in Aotearoa (aka New Zealand) where the term ‘coloured person’ is a common term used by non-white people from many ethnicities to describe themselves. I realise the term has a loaded history in reference to black people in North America, and that this blog has a further reach than Aotearoa, and will be changing the text in future printings and online once my repetitive stress injury is a bit better

“Where are you from?”

July 21, 2011 § 9 Comments

In response to your question: “Where are you from?”

Why do you ask?

Is it your curiosity in the ‘origin of my features’?

Is it your fascination for ‘other’ cultures and what they have to offer you?

Why do you desire an exact definition of my difference?

Why do you assume I desire, and am able, to define this difference to you?

Do you show the same interest in determining the ‘ethnic make-up’ of every white face that you see?

Isn’t everyone from somewhere?

Don’t you have a heritage?

Why does whiteness make yours invisible yet my brownness make mine subject to your anthropological investigation?

Do you believe that I should be delighted to personally inform and educate you?

Do you think it is my responsibility to know, and always be ready to impart, the details of my cultural heritage?

Do you apply these same standards to yourself?

Why do you assume that I’d love to reminisce about what my family, or I, left to come here?

Didn’t it cross your mind that we may have left for good reasons that I do not wish to reminisce about, especially with a stranger?

Do you believe your curiosity is commendable?

Do you think I should be grateful for your ‘tolerance’ and interest in ‘diversity’?

Do you believe this is YOUR country to welcome me to?

While brownness prompts

“Where are you from?”

Your whiteness prompts

“What do you do?”

You wish to define me by my physicality but you expect to be defined by your actions and your intellect.

Have you travelled the world and been asked the same question?

It isn’t the same experience in a place where you had expected to be treated as a visitor.

Perhaps your whiteness provided a fascination, but wasn’t it also exalted?

Weren’t you still treated like a speaker at a podium?

Or don’t you see this because you are so used to being heard from that position?

Don’t you realise that in expecting to discuss my brownness as subject of your fascination you position me as an exotic curio on a pedestal?

Do you think I wish to be a talking doll, spilling my secrets each time yet another curious child pulls my cord demanding that I politely answer your question?

………………………………………………

I performed the above piece at the RISE 40Hands book launch and poetry slam on the weekend. The publication features poems, mostly by detainees and ex-detainees, with additional contributions by people from POC migrant backgrounds, such as myself. I was lucky to participate in the series of RISE poetry workshops hosted by Pataphysics. Pata and many of the workshop participants performed on the night, as well as the always amazing Candy Bowers, the cutting Kojo, and the witty and charming Marissa Johnpillai, visiting from Aotearoa.

My poem is addressed to white people, like most of my poetry, but it’s not for them. Judging from the laughter it received from many people of colour in the audience (POCS made up the majority of attendees), the people I had hoped would get it, really got it. I did see some uncomfortable white people and this was unfortunately acknowledged by the MC, Victor Victor, after I left the stage, when he apologised if anyone was offended, because that wasn’t ‘our’ intention as it was a night about ‘positivity’. Ramesh, CEO and co-founder of RISE, did ask him to take back the apology, which he did the next time he was on stage. Is there any person, especially any white person, who couldn’t do with being challenged on their less obvious (to them) racisms? And how, and why, should I do that without making some people uncomfortable? Especially considering, as a person of colour living in a white-centric world, I’m always adapting to ‘uncomfortable’ circumstances.

I want to print the poem as a handbill, a kind of none-of-your-business card, to give out every time I get asked this question, à la Adrian Piper. I’d like to just walk away without having to verbally explain each time why that question is so loaded and why I am so reluctant to indulge the curiousity of the questioner.

I’d been having relevant correspondence with Wai Ho, who is part of Mellow Yellow blog, among other things. I sent them the poem and their email response ponders where that question comes from…

White people, especially in colonial settler societies, ask that question because it’s like closet homos that bully queers. Colonial settler society imbibes amnesia, because they would like to forget that they did indeed “come from” somewhere not so long ago, and that their “coming” was an invasion (which is why they get so touchy with Asian invasion). Also the shame/guilt they feel from leaving UK/Europe makes them extra touchy about things… They actively forget their shameful colonial histories, which is why they like to think they have no culture, because they’ve cut off their ethnic cultural limbs along with their colonial imperial invader hands.

White Australia makes such a big deal about ‘letting’ certain people into this country, actively forgetting this is not their country either.

RISE is a not-for-profit organisation founded and run by ex-detainees for refugees, asylum seekers and ex-detainees, making a rare, empowering structural choice of striving to function with little involvement by white ‘benevolence’ (which always enacts a power dynamic). Government policies and ‘Go back to where you came from’ attitudes are the obvious racisms that do-gooder white people love to point their fingers at, but institutional racism affects and infects us all. Finger pointing white people who wish to claim they are ‘not racist’ need to question their place in a system that places whiteness in the magnanimous ‘helping hand’ position and Indigenous and non-Indigenous people of colour as the should-be-grateful recipients of ‘tolerance’ and charity.

White people need to ask themselves why they expect gratitude for ‘giving’ access to the benefits of a country that white people stole and now most assume as their own. I don’t hear do-gooder white people who mostly call themselves ‘Australian’ even use the qualifier of ‘non-Indigenous Australian’ (though the term ‘Indigenous’ is also a white construct).

White Australia may forever be defining people who have come here because of circumstances they would probably rather not remember, as ‘refugees’. White people wish to forever remind people of their experiences of trauma, escape, re-location, and detention because it reminds themselves of their own ‘generosity’ in allowing people who ‘needed them’ to let them into ‘their’ country.

White people need to question their very curiousity in ‘other cultures’, because it’s a white-centric viewpoint that places people of colour as curious, unknown ‘other’ waiting to be ‘discovered’ by them, and the ways of whiteness as expected knowledge. No gratitude should be expected for this dehumanising other-ing of people of colour that comes with the normalization of whiteness.

White people recognise only the symptoms of systemic racism that register to their own perspective; physical violence, government policies, verbal intolerance and abuse, ‘obvious’ exclusion and discrimination; but there are other often indescribable power dynamics that I register in my daily lived experience which white people do not recognise, especially in their own behaviour. A white person may ask “Where are you from?” with ‘good intentions’, but ‘good intentions’ have always attempted to justify the oppression of people of colour. I recognise their invasive and other-ing curiousity in ‘different’ physicality as yet another symptom of a white supremacy in which I am made aware of my position within, and am expected to tolerate, every day.

Community: the illusion of inclusion

June 24, 2011 § Leave a comment

On the Queen’s birthday weekend I traveled to Sydney to perform at POC the MIC Sydney: “a performance night featuring people of colour spoken word, burlesque and more” that was held during Camp Betty “a radical political festival on sex, sexuality, gender and politics”. I read something close to the below text before performing my poetry and spoken word pieces, in regards to the context in which I was presenting.

For a few months now I have been creating poetry, spoken word and other writing under the name Harsh Browns about my experiences of racism. Much of my writing regards oppressive behaviours I’ve experienced from white people who consider themselves ‘progressive’ or part of ‘radical communities’.

It seems to me that there is comparative willingness for dialogue around politics of sex and gender but when it comes to talking about race, white people get really defensive or clam up, acting offended that I’ve challenged them because, they assert they’re ‘not racist’. As if a brown person couldn’t possibly have valid insight as to whether a white person’s behaviour may reflect institutional racism.

Most white people I’ve talked to seem to think racism is something other white people do. It’s a new experience for them to be challenged or what they feel is ‘misunderstood’ around issues of race.

And that’s in sharp contrast to my own lifetime of experience having my viewpoints regarding race so rarely affirmed or reflected back to me.

I’m sick of talking to white people about issues when they’re not considering how race relates to the conversation. I’m even more tired of talking to white people specifically about issues of race. We don’t begin the conversation on equal footing and I have so much more to emotionally risk from the ‘discussion’, that seems to change nothing except to increase my sense of alienation.

It’s more empowering for me to create art and writing about my experiences. Not for white people to understand me. Instead, I make it with hope that it’s for people who share my frustrations.

An event like POC the MIC that is organized by and features only people of colour, that prioritises people of colour first, each of us presenting our varied experiences, is personally empowering for me after spending so much time in supposedly ‘radical’ spaces in which I may be told I’m welcome but where white people are used to taking up most of the space and having their voices heard most of the time.

I performed the poems and spoken word pieces that I’ve posted on this blog. The night was personally empowering. Hearing the pain, anger, and other emotions in the voices of so many people of colour performing, as varied as each of our experiences are, was painfully affirming of my own feelings. Hearing the responses of other people of colour to my own performance was affirming of the energy I’ve been putting into writing about my experiences.

I feel like holding the details of these personal exchanges to myself and to those close to me. I came away from the weekend with a realisation that this permutable network of my own interpersonal relationships is the only concept of ‘community’ to which I feel comfortable to claim a sense of belonging. I feel affirmed that my feelings of anger at, and alienation from queer and radical communities, as I have known them, are justified. I feel empowered to let go of the expectation of ‘inclusion’ in what others consider ‘our community’. I’ve tried for so long to believe otherwise, but it’s always been a peripheral existence. I’ve never had the feeling of ‘home’ that I hear many others speak of in regards to ‘queer’, ‘punk’, and other ‘radical communities’, though I’ve inhabited spaces identifying as such, because of aspects of my own identity. Many people seem to speak with an assumed sense of belonging to ‘our community’, a sense that I suspect is linked to privilege that I have not experienced. When people speak of ‘our community’, I hear them speak of their idea of community. When white people ponder “What our community needs to do to be inclusive of people of colour…”, they centre whiteness in ‘our community’, and the conversation, and I feel further marginalized. I’m not interested in being ‘included’ on these terms, to be allowed onto the peripheries of an illusion of community that I do not believe in.

Many people who consider themselves ‘radical’ seem to speak of their idea of community as if it is an independent entity that is possible to exist, for the most part, exclusive of the oppressions they associate with broader culture. If there is anything more than a nod of acknowledgment of oppression within their idea of community, many individuals seem unable to acknowledge their own oppressive behaviours, nor their privileges. I’ve been to enough spaces that aim to provide a ‘safer space’ from x, y and z phobias and from racism, but in regards to my sense of alienation in that space, I may as well have been walking down Swanston Street in Melbourne city on a Friday night. At least there I wouldn’t have an expectation of belonging, one that is never fulfilled.

I’ve realised that I can only try to find a sense of ‘home’ within myself. And I did feel that sense of home within myself in the empowering space of POC the MIC. I don’t consider the people who performed and organised to be part of a ‘person of colour community’. I’m not falling for another illusion of community that expects a sense of belonging that will eventually disappoint. These realisations are not sad, nor individualistic; I will happily put my energy and support into relationships and projects, with individuals that reciprocate these energies, without defining my interpersonal networks as a ‘community’. It is not from a lacking in me that I claim not to belong to a ‘community’, it’s the ‘communities’ that are lacking, and it’s an empowering choice to claim ‘I do not belong’ to a community, only to myself.

“I’m not racist”

June 22, 2011 § 10 Comments

I hear this line of defense so often when I challenge white people on racist behaviours. I had the privilege of listening to a recording in which Tracey Bunda, speaking on a panel “Women of the First Nation” that opened the Feminist Futures conference, broke down how it is that white people exercise privilege in saying these words.

How is feminism relevant to Aboriginal people’s lives? Whose purpose and for what purpose is being served when Aboriginal people come into this space? In crossing over into a feminist space what risks are hidden that we may have to come face to face with? And we usually do that alone as Aboriginal woman. And in raising this matter I think how permanent a fixture being raced, moving into racialised spaces and how race takes a very different shape to say, the time in which my mum grew up which was 1920’s and even the time in which I grew up in the 19 – I’m not telling you.. (laughter). But it’s still very insidious within Australian society and it takes a very different shape.

You know, it’s easy to look at somebody like, what’s-his-face, an Andrew Bolt, but it’s those very insidious forms of racism that have become very sophisticated, and they are framed within politically correct, ‘colour-blindness’, and it’s those sorts of racisms that Aboriginal people deal with, and non-Indigenous people deal with, and part of the privilege is to be able to say “No, I’m not racist”.

(later, during question time, in response to audience member asking Tracey to expand on ‘the privilege of being able to say “I’m not racist”’…)

When we challenge a person on their behaviour and that person responds back to us by saying “I’m not racist”, it’s an exercise of power to shut down the conversation. Right? Because, the person who is saying that, and it’s usually a white person, wants to hold, wants to be centred and dominate virtue. And so that behaviour of goodness is always then attributed to whiteness. And then in challenging white people by saying “That behaviour is racist. What you have just said is racist”, there’s this retreat to virtue and a retreat to goodness to dominate that particular space. And so, in dominating that space; “No, I’m not a racist”, what becomes unspoken is that “You’re not virtuous because you are not engaging in polite conversation with me. You’re actually wanting to disclaim my virtue. You’re bad”. And blackness is associated with bad.

– Tracey Bunda, a Ngugi Wakka Wakka woman and Associate Professor of the Yunggorendi Centre at Flinders University, speaking on panel “Women of the First Nation” which opened the Feminist Futures conference that was held end of May in Melbourne. Notated with her permission.

I don’t want a piece of the cake…

June 15, 2011 § 4 Comments

The Recipe

No reason to

Expect respect

You never gave

Me it before

You stroke my arm

Treat me as a child

You help yourself

Say you know best

Your kindly tone

Belies the truth

Your gratitude

Has attitude

At any rate

It’s all for you

While I should know

I am lucky

To get pity

Should be thankful

For a handful

You let me take

A slice of cake

Your recipe

Unshared with me

You live by rules

Entitled to

Believe they are

Applied the same

To me and you

And I have tried

To believe this lie

Swallowed each sigh

Inside myself

All my life

Now your surprise

That I go wild

Out of control

Of your control

You try to keep hold

Choose to dismiss

My anger blind

Myself unkind

The blame on me

For rejecting

All your offers

Of unity

Your offers that

Delete dissent

Refuse critique

Especially

Without comedy

Or calm relay

In any words

However said

You are content

To see yourself

As innocent

The world you know

Supports your view

So I suspect

You won’t take time

To self reflect

My rage is real

And justified

And every day

The world I knew

Including you

Compounds my view

I know that I

Can’t change the world

That includes you

But I can try

To change my world

To exclude you

As you did me

Though you don’t see

My sights are clear

All I expect

Is what I give

My self respect

……………………

I wrote the above poem in consideration of my many interpersonal relationships with people whom have not allowed space and understanding for my anger over institutional racism, that I see clearly reflected in the dynamics between us, yet they do not.

The poem references a quote by comedian Paul Mooney, “I don’t want a piece of the cake, I want the fucking recipe” from his stand-up CD ‘R A C E’ (1993). I realised after writing it, that race is not explicit in the poem. Several people have commented to me, after performing it at POC the MIC Sydney last weekend, that they heard it as reflective of their own lived experiences of oppression, not necessarily to do with race. I wrote it for those who share the frustrations of exclusion to do with race, but recognise that there are many oppressions that contribute to people experiencing anger about their alienation.